Doug Kerr

Well-known member

[One of a series]

At least in the United States, practical "home movies" were made possible by the introduction, by Eastman Kodak Company, in 1923. of 16 mm motion picture film. Previously, motion picture filming was primarily done with 35 mm film.

The 16 mm format naturally made practical smaller, lighter, and generally less expensive cameras (and certainly projectors). And, for a given running time, the 16 mm format used (in terms of film stock area) only about 18% as much film stock as the 35 mm format, resulting in a substantial (if not proportional!) reduction in the cost of film and processing.

At this time, Kodak introduced its first "home movie" camera (using the new 16 mm film), which was quickly followed by another model, smaller, lighter and easier to use. We will hear more about this in a later section of this series.

Still, the cost of 16 mm cameras, and the cost of 16 mm film and its processing, were not economically attractive to the widest range of potential users, and so, to further reduce the cost of "home movies", Kodak introduced, in 1932, 8 mm motion picture film. This of course resulted in a further reduction in the size, weight, and cost of cameras, and a reduction in the cost of film and its processing.

As you can well appreciate, in order to avoid a substantial deterioration of image quality with this format, a film stock with substantially finer grain had to be developed for this format, and improvements needed to be made in the steadiness of film registration in economical cameras and projectors.

The common way in which 8 mm film was provided was under the "dual 8 mm" scheme. Here, the film (typically 25 feet, plus some extra for leader and trailer, on a spool) was actually 16 mm wide. But the perforations (on both edges) were at essentially half the pitch as for 16 mm film (the frame pitch for the 8 mm format).

The film was loaded in the camera, and when run, resulted in frames being recorded done one side of the film. When all 25 feet had been shot (a little over 2 minutes of shot time!), the camera was opened, the takeup reel (nor carrying all the film) was mounted (other side up) as the supply spool and the camera rethreaded.

On this pass, the frames were recorded alongside those recoded in the first "pass".

At the processing laboratory, the film was processed intact , and was then slit lengthwise to provide two 25 foot lengths of 8 mm film. These were then spliced end-to-end (a total length of 50 feet, with a run time a little over 4 minutes, the same as for 100 feet of 16 mm film), spooled onto a nice reel, and returned to the user.

The first Kodak 8 mm motion picture cameras, the Ciné-Kodak Eight series, was also introduced in 1932. There were two almost identical versions, the Model 20 and Model 25, differing only in the lens with which they were equipped (a fixed-focus Kodak Anastigmat 19 mm f/3.5 in the Model 20 and a fixed-focus Kodak Anastigmat 19 mm f/2.7 in the Model 20.

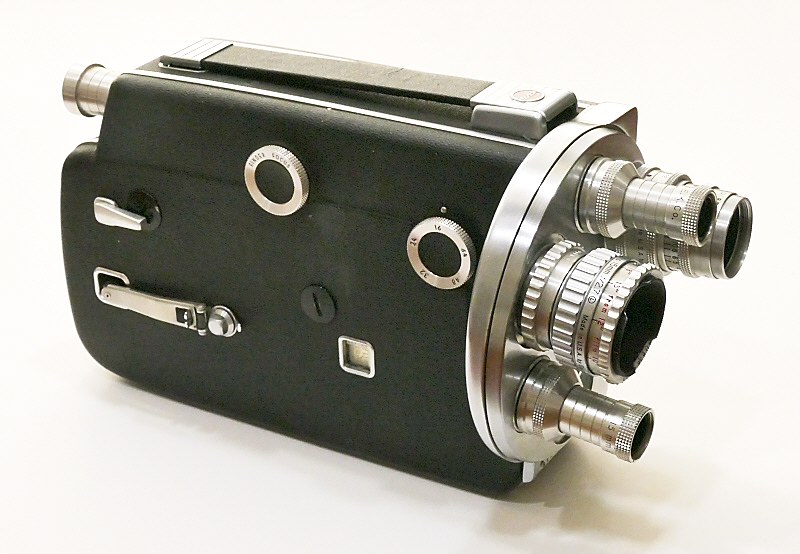

Here we see, from our personal collection, a Ciné-Kodak Eight Model 25, believed to have been manufactured in 1937.

Douglas A. Kerr: Kodak Ciné-Kodak Eight Model 25 motion picture camera

The camera was powered by a spring motor, wound with the key we see here. The chrome button, which pushed down, made the camera run; it could be pushed past a detent so it would remain in the "run" position so, with the camera on a tripod, the operator could get into the scene.

The camera was equipped with a folding, open viewfinder of the "reverse Galilean" type, actually integrated into the handle arrangement. With the handle raised, the viewfinder was erected for use. We will see it lowered in the later photos.

Here we see a better view of the front of the camera.

Douglas A. Kerr: The aperture nameplate

We see that the nameplate on which the camera aperture settings are presented has, for each one, a description of a scene and situation for which the exposure resulting from that aperture would likely be appropriate. The camera ran at only one frame rate (nominally 16 fr/s) and had a fixed "shutter angle", so the exposure time was fixed, about 1/30 s. And these exposure recommendations were predicated on the speed of a single type of film, Kodak Panchromatic (B&W), which was the primary type of film available at the time for this camera. (Kodachrome color film was not been introduced until 1935.)

The manual, of course, gave further subtleties of exposure planning, including discussion of how to deal with the ambient lighting conditions when shooting in the tropics in summer. But the guidelines on the aperture plate were valuable for the user who didn't happen to have the manual in her skirt pocket.

Here we see the interior of the camera, the left side panel having been removed for access for loading the film. The film transport mechanism is unique.

Douglas A. Kerr: The camera interior

For comparison, we note that in "professional" 8 mm motion picture cameras (such as the Paillard-Bolex H8), a rotating sprocket (fairly small in diameter) is used to pull the film from the supply spool and send it at exactly the correct rate toward the intermittent motion film gate. A second small sprocket was then used to govern the movement of the film from the gate to the takeup spool.

In cameras such as the early Kodak 16 mm cameras, a single small sprocket served both these purposes, the film having a brief engagement with it on the way from the supply spool to the gate and a second brief engagement with it on its way from the gate to the takeup spool.

And in later 8 mm cameras, there were no sprockets at all. The motion of the film was solely propelled by the intermittent motion in the gate (ugh!).

But in the Ciné-Kodak Eight cameras, there was a single sprocket, but of really large diameter. The design strategy behind this escapes me. But it is certainly pretty.

We also note the marking on the takeup spool reminding the user that it we see that spool full, it means that this is only the end of the "first pass", and that the film has to be reloaded for the second pass.

Of course at the end of the second pass, this spool is empty, and is retained by the user, it being the permanent takeup spool for this camera.

This lovely camera was a Christmas gift, in the early 2000s, from Larry Henry, Carla's son. I am embarrassed to say I did not give it the attention it deserves until just recently.

[to be continued]

At least in the United States, practical "home movies" were made possible by the introduction, by Eastman Kodak Company, in 1923. of 16 mm motion picture film. Previously, motion picture filming was primarily done with 35 mm film.

The 16 mm format naturally made practical smaller, lighter, and generally less expensive cameras (and certainly projectors). And, for a given running time, the 16 mm format used (in terms of film stock area) only about 18% as much film stock as the 35 mm format, resulting in a substantial (if not proportional!) reduction in the cost of film and processing.

At this time, Kodak introduced its first "home movie" camera (using the new 16 mm film), which was quickly followed by another model, smaller, lighter and easier to use. We will hear more about this in a later section of this series.

Still, the cost of 16 mm cameras, and the cost of 16 mm film and its processing, were not economically attractive to the widest range of potential users, and so, to further reduce the cost of "home movies", Kodak introduced, in 1932, 8 mm motion picture film. This of course resulted in a further reduction in the size, weight, and cost of cameras, and a reduction in the cost of film and its processing.

As you can well appreciate, in order to avoid a substantial deterioration of image quality with this format, a film stock with substantially finer grain had to be developed for this format, and improvements needed to be made in the steadiness of film registration in economical cameras and projectors.

The common way in which 8 mm film was provided was under the "dual 8 mm" scheme. Here, the film (typically 25 feet, plus some extra for leader and trailer, on a spool) was actually 16 mm wide. But the perforations (on both edges) were at essentially half the pitch as for 16 mm film (the frame pitch for the 8 mm format).

The film was loaded in the camera, and when run, resulted in frames being recorded done one side of the film. When all 25 feet had been shot (a little over 2 minutes of shot time!), the camera was opened, the takeup reel (nor carrying all the film) was mounted (other side up) as the supply spool and the camera rethreaded.

On this pass, the frames were recorded alongside those recoded in the first "pass".

At the processing laboratory, the film was processed intact , and was then slit lengthwise to provide two 25 foot lengths of 8 mm film. These were then spliced end-to-end (a total length of 50 feet, with a run time a little over 4 minutes, the same as for 100 feet of 16 mm film), spooled onto a nice reel, and returned to the user.

The first Kodak 8 mm motion picture cameras, the Ciné-Kodak Eight series, was also introduced in 1932. There were two almost identical versions, the Model 20 and Model 25, differing only in the lens with which they were equipped (a fixed-focus Kodak Anastigmat 19 mm f/3.5 in the Model 20 and a fixed-focus Kodak Anastigmat 19 mm f/2.7 in the Model 20.

Here we see, from our personal collection, a Ciné-Kodak Eight Model 25, believed to have been manufactured in 1937.

Douglas A. Kerr: Kodak Ciné-Kodak Eight Model 25 motion picture camera

The camera was powered by a spring motor, wound with the key we see here. The chrome button, which pushed down, made the camera run; it could be pushed past a detent so it would remain in the "run" position so, with the camera on a tripod, the operator could get into the scene.

The camera was equipped with a folding, open viewfinder of the "reverse Galilean" type, actually integrated into the handle arrangement. With the handle raised, the viewfinder was erected for use. We will see it lowered in the later photos.

Here we see a better view of the front of the camera.

Douglas A. Kerr: The aperture nameplate

We see that the nameplate on which the camera aperture settings are presented has, for each one, a description of a scene and situation for which the exposure resulting from that aperture would likely be appropriate. The camera ran at only one frame rate (nominally 16 fr/s) and had a fixed "shutter angle", so the exposure time was fixed, about 1/30 s. And these exposure recommendations were predicated on the speed of a single type of film, Kodak Panchromatic (B&W), which was the primary type of film available at the time for this camera. (Kodachrome color film was not been introduced until 1935.)

The manual, of course, gave further subtleties of exposure planning, including discussion of how to deal with the ambient lighting conditions when shooting in the tropics in summer. But the guidelines on the aperture plate were valuable for the user who didn't happen to have the manual in her skirt pocket.

Here we see the interior of the camera, the left side panel having been removed for access for loading the film. The film transport mechanism is unique.

Douglas A. Kerr: The camera interior

For comparison, we note that in "professional" 8 mm motion picture cameras (such as the Paillard-Bolex H8), a rotating sprocket (fairly small in diameter) is used to pull the film from the supply spool and send it at exactly the correct rate toward the intermittent motion film gate. A second small sprocket was then used to govern the movement of the film from the gate to the takeup spool.

In cameras such as the early Kodak 16 mm cameras, a single small sprocket served both these purposes, the film having a brief engagement with it on the way from the supply spool to the gate and a second brief engagement with it on its way from the gate to the takeup spool.

And in later 8 mm cameras, there were no sprockets at all. The motion of the film was solely propelled by the intermittent motion in the gate (ugh!).

But in the Ciné-Kodak Eight cameras, there was a single sprocket, but of really large diameter. The design strategy behind this escapes me. But it is certainly pretty.

We also note the marking on the takeup spool reminding the user that it we see that spool full, it means that this is only the end of the "first pass", and that the film has to be reloaded for the second pass.

Of course at the end of the second pass, this spool is empty, and is retained by the user, it being the permanent takeup spool for this camera.

This lovely camera was a Christmas gift, in the early 2000s, from Larry Henry, Carla's son. I am embarrassed to say I did not give it the attention it deserves until just recently.

[to be continued]