In 1907, Henry Ford began the design of what we would today call an internal combustion tractor, visualizing that it would revolutionize agriculture (at the time wholly dependent on the horse, mule, and ox for tractive effort).

In 1920, Ford, with his son Edsel, founded Henry Ford and Son to pursue the tractor business. Design was put in the hands of the two principal designers of the successful Ford Model T automobile (both born in Hungary, by the way).

In 1916, the company introduced the Fordson Model F tractor, which did for the tractor business what the Model T had done for the automobile business. Henry Ford and Son was absorbed into Ford Motor Company in 1920, but continued the Fordson brand for its tractors for some while. Later models carried the Ford brand, and the Fordson brand was discontinued in 1964.

We are fortunate here in Weatherford, Texas to have a nice specimen of a Fordson Model F on display by the city in front of the old municipal generating station.

Douglas A. Kerr:

Fordson Model F tractor

I suspect it was made in about 1924.

This specimen had been equipped with a White Tractor Hoist, made by Oklahoma Engineering and Foundry Company, Muskogee, Oklahoma. It is actually what we would today call a winch. We see it here:

Douglas A. Kerr:

Fordson Model F tractor - White Tractor Hoist

The mechanism was driven by the tractor's power takeoff output shaft. Power takeoff on those days was by way of a pulley on the side of the tractor, driven by a shaft coming out the side of the transmission (there was an internal clutch in the path) which drove (stationary) agricultural machinery by way of a leather belt.

In this case, that shaft is commandeered to drive a chain leading to the rear (see the chain housing on the right of the figure). The winch drum was mounted coaxially with the left axle, inboard of the left wheel. Very clever (likely designed by a Cherokee).

A sliding pinion (running on a fat splined shaft) would be engaged to a large gear on the drum to enable the hoist system. Actual hoisting, though, was controlled by the power takeoff clutch. A band brake was used to control payout of the cable (we see the lever for engaging the drum drive pinion reaching around it - the Cherokee are eminently practical).

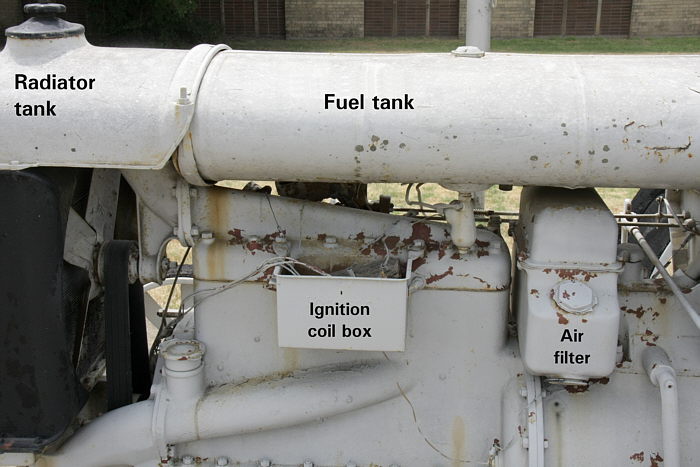

Here we see, from the left side, some interesting features of the engine:

Douglas A. Kerr:

Fordson Model F tractor - left side of engine

Above the radiator was a quite large water tank, with an oval cap intended to allow easy filling with a bucket. There was a large fuel tank; the engine ran on what was essentially kerosene.

Induction air was cleaned by bubbling it though a tank filled with water.

The ignition system was like that of the Model T. There was an ignition coil for each spark plug (this is a four-cylinder engine, about 20 hp). Each coil, in a nice wood box, with dovetail joints at the edges, and filled with tar (I can today conjure up the strange scent of that combination), has a moving armature with a normally closed contact in the primary circuit of the coil, so that when energized it would cycle like a buzzer, developing a train of high voltage pulses at the secondary.

A timer, mounted where we would later have the distributor, fed battery voltage to the coil for each cylinder when it was time for it to fire.

The terminals of the coils were flat lead domes, reminiscent of the center contacts on old incandescent lamps.

The coils were placed in a steel box, and a wood cover equipped with contact springs brought the primary and secondary leads to each. Thus any of the coils could be easily replaced if needed, or removed to fiddle with the "buzzer" contacts.

By the way, the Fordson Model F had no brakes for the tractor itself. The final drive (in the differential) was a worm gear arrangement. Because of the frictional properties of a worm drive, it would not allow "backflow" of motion. When the drive clutch was released (with a pedal, in the modern style), the tractor came to a stop, even if on an incline.

Eugene Farkas, the principal engineer (as I said before, of Model T fame) is credited with first using the engine crankcase, the transmission, and the differential (all quite robust) as a monolithic structural member, completely eliminating the need for any other frame at all. This became common on most agricultural tractors from then on - the drive train

was the frame.

Best regards,

Doug